Clicca qui per l’articolo in italiano sul blog del festival Attraversamenti Multipli

by Ornella Maggiulli with Julio Ricardo Fernandez, Ali Jubran, Federica Mezza, Matteo Polimanti, Mahamadou Kara Traore, Jack Spittle

English translation by Velia Cimino

H 20.00 – Who’s at Largo Spartaco, and what have they done to the wall? There are the Quadraro residents and not only. There are those who have come for Antonio Rezza – his show will start in an hour, opening Attraversamenti Multipli 2021 – and those who came to populate the square minding their own business, as they do every day. In fact, we all sit on the low wall bordering the square, recently repainted by BOL, who has left black spaces in his work, inviting the residents to fill them with their thoughts, which are often poems. BOL’s street art work is entitled RAINBOW – a work to inhabit. No sooner said than done.

Quadraro women sit next to the new artwork RAINBOW – a work for living by BOL

H 21.00. How many people came to see Rezza’s Asta al Buio? Whether they were many or few, they were certainly a variety. For example, who would bet half a penny on nothing? Someone did it for Rezza, ask them why. Among the audience raising their hands (and their stakes) to grab unannounced auction items (some found out they had won a Kindle and others a bag of “nothing”) was Mamadou Kara from our editorial staff, who remarked at the end of the show: “I didn’t understand why people raised their hands! I didn’t understand the game at all, how did [Rezza] manage to do a dozen auctions and have people go and give money at random? What if that money was asked for by someone who really needed it? I’m not comparing the situation, but what if someone who washes cars windows at the traffic lights did it? They wouldn’t get a dime. But they had the courage to do it, to me it’s a joke, it’s madness. They raised their hands without even considering whether they had cash or not. I don’t know what the actor’s trick was. I wouldn’t do it… in the middle of so many people, in a square, I keep quiet. I wouldn’t go!

More than one person raises the stakes blind on Antonio Rezza’s play Asta al Buio (Blind auction). Real money, not always the same as for prizes

We wondered: wasn’t the “trick” of the show’s success precisely that of being able to demonstrate that the price of an experience (which in this case can be a hoax by Rezza) is decided by each one individually? It must have been human inconsistencies that arose from this consideration, from this “joke” as Kara put it, which in the end made everyone laugh.

Laughing person at Rezza’s show Asta al Buio (Blind Auction) – probably someone who did not bid at the auction

The show, like the square, is pervaded by many people’ s thoughts. Each one has his or her own reasons for attending, his or her own experiences and moods for judging. Who would you trust if you were to ask the many people in the show and in the square “What is it like?” It may sound frustrating, but they would all be right. Rezza has just provided the first example to appreciate the declinations of this matter of fact within our Mestizo editorial staff.

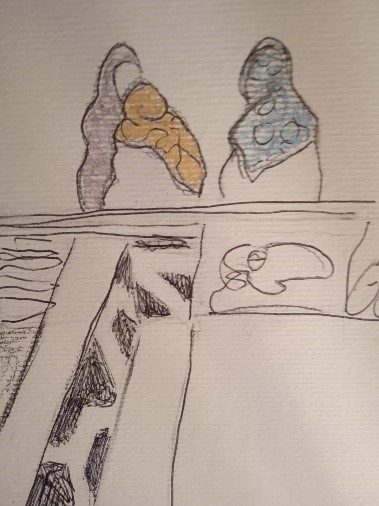

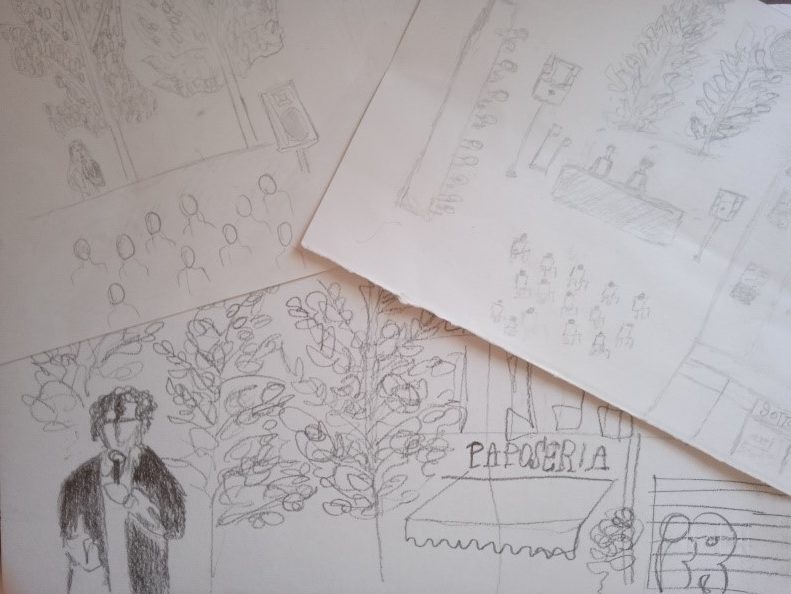

Ali, Giorgio and Ornella were one evening watching the same performance, i. e. Antonio Rezza’s Asta al Buio at Largo Spartaco. Does it show by looking at their drawings? Imagine their own personal impressions…

H 22.30. Consumption of meat and its production process is a familiar topic. But in what ways has it been described? In what ways is it still possible to do it, and what to expect from the public? Carlo Massari proposed his own way in Mash-up. A way consisting in flesh and bones – his own – which embodied a whirlwind of knees, knuckles and ass on the concrete of GarageZero. A slaughterhouse dance.

“The image I saw when he [Carlo Massari] was trembling, a baby cow. Seeing his legs shaking, I saw a newborn cow, as I have seen so many down home. Yes, they do that”. “For Kara, ‘down home’ means in Mali, where in his memories seeing a cow is more likely than eating one. Jack, on the other hand, was brought up in the United States, where the opposite is true. Indeed, Jack admits that ‘because of this show, over the last couple of days I’ve been plunging into some memory sites I haven’t visited in who knows how many years. I wrote to four uncles, two cousins and several friends. I started writing food-related memories and I still can’ t stop, I’m up to seven files of aphorisms! A good exercise’. A wonderful interview with Carlo Massari by Kara, Jack and Giorgio is also a taste of all the different facets of meat from Mali to the United States, and is highly recommended (here, Beyond my meat. A dialogue with Carlo Massari).

Carlo Massari caught in a rare snapshot of him standing still in his Mash-up show

Using one’ s own body to talk about other bodies – in this case non-human bodies – proved to be, intentionally or unintentionally, a successful way of overcoming moral questions about meat consumption which have often become rhetorical, by managing to simply focus on evoking and comparing experiences. Little did we know that simple bodies and games, such as the circus ones, would be the pivot of our main considerations in the days to follow.

H 18.00. There were two people there, a brakeless bike, a log and an electric saw in the middle of a circle made up of many children..

Unauthorised portrait of the circus duo Rasoterra

How much does being together mean supporting each other to look further afield, even in opposite directions if needed? The Rasoterra duo, in Happiness, seemed to suggest that it is such a funny balance that it matches circus art.

The well-matched circus duo Rasoterra as they discover who knows what in their Happiness number, in defiance of gravity. As Rezza would put it, their pleasure is everybody’s pleasure.

Reflecting on her impressions during the performance, Federica says: “When I watch two performers doing peculiar acrobatics using their bodies in a ‘spectacular’ way, I am always struck by the knowledge they both have of each other’s bodies: their weight, the strength needed to support it, the bending of knees or elbows they have to use for such an acrobatic stunt. I would imagine how many rehearsals they have had to do to succeed in performing such a stunt, and how their bodies have memorised all the steps needed to reproduce those movements in order to succeed each and every time. It’ s all about connection, intimacy and trust.

In this interview (here, Happiness! How children watch) you can better understand how children – and not only children – watched and described Rasoterra’s Happiness (unpublished audio files included).

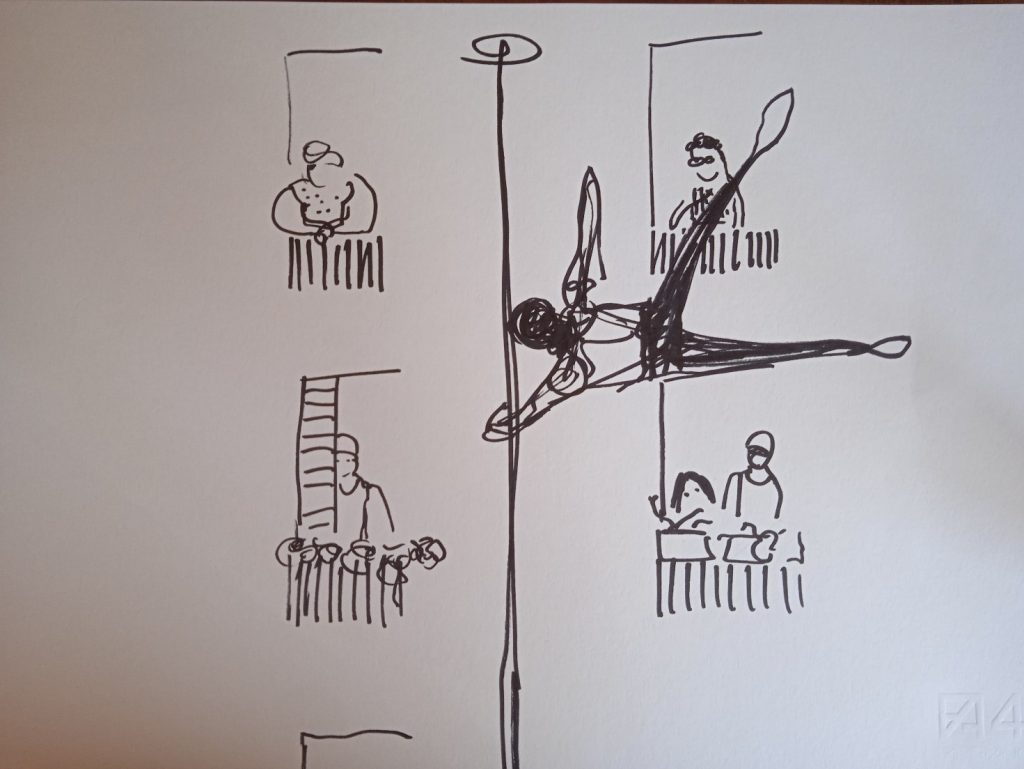

H 17.30. On an unsteady pole, held in balance by ropes pulled by eight spectators chosen by chance and not out of experience, a man was performing dangerous stuff in the middle of Largo Spartaco. Who was watching?

Cast the first stone who, living in the Largo Spartaco’s Boomerang, would not have looked out to see Mistral hanging from an almost two-storey high Chinese pole in Trust Me!

Julio, in drawing in words the scene that impressed him most from Mistral’s performance Trust Me, captures its essence and its effect on the audience: ‘he let himself fall head over heels, coming down with only his legs wrapped around the pole, without using his hands. Everyone looked at him, at the pole and at the ground. He let himself fall down confidently and trusting in himself and the others. It was beautiful, all eyes just looking at one spot.”

With the well-calibrated madness of a circus performer, clearly an expression of a mindset far more trained than normal in the ability to control reality, Mistral dived headfirst from his ‘Chinese pole’ at least twice. As Matteo describes, ‘Maya looks up. She is worried, but also curious to see how it will end. A strong mistral is blowing at the top of the pole. But sure, it would probably be all right. Maya is the little girl in the audience to whom Mistral said “Come here, do this with your hands and wait!”. The “so with your hands” is illustrated by Matteo below. Maya did “like this with her hands” in such an instinctive and hilarious way that she looked as if she couldn’t wait to pick up the seventy or so human kilos that would fall on her from above. By behaving in this way, Maya perhaps unwittingly revealed why Mistral relies on children to play this role of pick-me-ups. Mistral’s head, after a rapid acceleration, came to a sudden stop at a safe distance, well under a metre, from Maya’s little hands. Yes, everything went well.

In reality, Maya ran away right at the end, giving up her place to another child, but for the sake of narrative simplicity and not to diminish her laudable impulse to extend her arms to help Mistral in Trust Me, we have cut it short in the text.

Prity says: “When I watched the performance I was reminded of my childhood; when I was eight years old I went to the circus with my father”. If Mistral had happened to perform some 20 years ago in Bangledesh, he might very well have chosen Prity as his helper, as he did with Maya and the eight adult ‘pole bearers’ who were summoned to be responsible for his safety as well as the show’s dignity.

One of the pole bearers, whom Mistral trusted and vice versa, was Ali. “It has been a very nice and quite an unusual day for me. First of all, Mistral is a very nice and funny person. The unusual thing is that I participated with him in the parade and with my friends I wore the yellow jacket (the safety vest). When Mistral was handing out the yellow jackets, I felt he was going to give me one. I was worried, I didn’t know what would happen because I don’t speak Italian well, and I was afraid of being embarrassed in front of the public; but when he came up to me and gave me the jacket, I “became real”, I left my fears aside, I found a new courage and I stepped forward”.

Knowing how to build mutual trust, out of a momentary need but using the best means available, is perhaps also a circus art. To find out more, read the mestizo editorial staff’s interview with Mistral on his show Trust me (here, Trust me. On the rope between artist and audience with Mistral).

H 18.30. How much strength is needed in being sensuous? If our bodies weren’t already enough of an accomplice in pondering our contradictions, someone discovered it in Giorgia Celli’s open flamenco lesson. An hour of sweating regardless of gender or age.

H 20,30. And how much grace does it take to trot? In trotting around. At the end of the performances in the square, Giulio and Jari of the C.G.J Collective in the low lights hinted at how much study there is in re-presenting an apparent chaos. Which, if you look closely, is made up of a harmony of bodies talking to each other..

Try ‘trotting’ in coordination with a friend without making any noise or losing your rhythm, like Giulio and Jari of the Giulio and Jari Collective.

What about you, were you at Attraversamenti Multipli last weekend and did you draw pictures to capture something that struck you? Or did you capture scenes, details on which you then embroidered your thoughts? Whether I was there, whether I did it or not, as Jack would say, it’s a “good exercise”.

Ornella Maggiulli

con Julio Ricardo Fernandez, Ali Jubran, Federica Mezza, Matteo Polimanti, Mahamadou Kara Traore, Jack Spittle

photo Carolina Farina

This website is one of the final products of the project “LiteracyAct – Basic literacy, transversal skills and competences for adult migrants”, Erasmus Plus KA2 Adult Education N.2020-1-IT02-KA204-080084

Disclaimer

The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein